7. Dialogues

WME provides very powerful dialogue capabilities and this chapter deals with the way how you can implement dialogue trees in your game. We’ll use our last example where we have in one scene Molly and Sally.

Our chapter starts similar to the previous with the definition of so called “response box”. It’s the interface which will have stored the dialogue choices player has to make to successfully communicate with another character.

You’ll see that it’s very similar to the inventory box definition. We’re speaking about the file located in data\interface\responses.def and as we’ve seen already, it’s assigned in the Project Manager as the Response Window.

RESPONSE_BOX { FONT = "fonts\outline_white.font" FONT_HOVER = "fonts\outline_red.font"

Path to the font files used for the dialogue options and dialogue options with mouse hover.

HORIZONTAL = FALSE

Horizontal specifies if the dialogue options are to be displayed horizontally or vertically.

SPACING = 5

How many pixels should be the options apart?

AREA {40, 0, 800, 170}

Same as in the inventory box, you define the window in which your options appear.

WINDOW { X = 0 Y = 420 WIDTH = 800 HEIGHT = 180 BUTTON { TEMPLATE = "ui_elements\template\but.button" IMAGE = "ui_elements\arrow_up.bmp" TEXT = "" NAME = "prev" X = 0 Y = 0 WIDTH = 30 HEIGHT = 30 } BUTTON{ TEMPLATE = "ui_elements\template\but.button" IMAGE = "ui_elements\arrow_down.bmp" TEXT = "" NAME = "next" X = 0 Y = 150 WIDTH = 30 HEIGHT = 30 } } }

Again you see that there’s a window definition with two buttons (prev and next) which are the scroll buttons. If WME finds buttons named like this, it uses them automatically. All the positioning (absolute in window and relative in buttons is the same as with the inventory box).

From other possible options you can use:

TEXT_ALIGN - specifies the alignment of textual response lines; it can be either "left", "right" or "center"; the default value is "left"

VERTICAL_ALIGN - specifies the vertical alignment of responses within the response area (it has no effect on horizontally ordered items); it can be one of the following values: "top", "center" or "bottom"; the default value is "bottom"

Of course you can for the window use IMAGE parameter which would set some background image for the response box. I’ll leave it to your imagination for now and let’s move on the way how the dialogue itself is constructed.

Dialogues in WME are entirely scripted which give them a huge flexibility. You can do whatever you like, in the middle of the dialogue including running complex cut-scenes, videos, you name it - you have it.

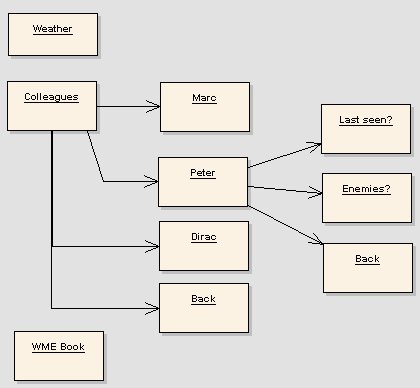

But back to our dialogue - let’s look at a sample dialogue tree I’ve created for this purpose:

This is the typical way how can player traverse the dialogue tree. He can either ask about Weather or Book or he can ask about his colleagues which opens him a path to ask about specific colleagues and moreover Peter opens up way to some plot like elements.

Also we’d like to define some other rules to our dialogue. Weather is very stupid topic so we’d let our player as about it only once per the whole game. Marc and Dirac are not important for the story, so we’ll let the player ask about them only once per dialogue. Lastly “Book” topic will be opened to player only when Molly picks up the book.

So let’s get moving. We have to be familiar with a few new methods:

Game.AddResponse([response number], [response text]); adds a response to the response window.

Game.AddResponseOnce([response number], [response text]); adds a response to the window once per the current dialogue branch. Then the topic disappears until you leave the dialogue branch.

Game.StartDlgBranch(); is a method used when you want to start a dialogue branch for use with AddResponseOnce method.

Game.EndDlgBranch(); is a method used when you want to end a dialogue branch for use with AddResponseOnce method.

Game.AddResponseOnceGame([response number], [response text]); adds a response to the window one per the whole game.

Game.GetResponse(); Displays the prepared dialogue box, waits until player selects a response and returns the selected response number.

Because we want to keep our code clean, we’re going to use separate functions for all tree levels, we’ll call this functions “basic”, “Colleagues” and “Peter” to easily distinguish them.

But enough chit-chat, open up the sally.script and let’s keep moving. Erase everything in this file and leave there something like this:

#include "scripts\base.inc" on "LeftClick" { basic(); }

Good start, isn’t it? Well, we’re going to add something more obviously. Let’s start with the function basic();

function basic() { var options; options[0] = "Nice weather, isn't it?"; options[1] = "Can you tell me anything about your colleagues?"; options[2] = "What's this book for?"; options[3] = "Bye!"; var selected; while (selected != 3) { Game.AddResponseOnceGame(0,options[0]); Game.AddResponse(1,options[1]); Game.AddResponse(3,options[3]); Game.Interactive = true; selected = Game.GetResponse(); Game.Interactive = false; actor.Talk(options[selected]); // actor says the selected line first switch (selected) //we choose what to do based on the selected option { case 0: sally.Talk("Not really"); break; case 1: sally.Talk("Who exactly is of interest to you?"); break; case 3: sally.Talk("See ya!"); break; } } Game.Interactive = true; }

First we’ve created an array called options. This is very useful not only for the keeping texts tidy and in one place, but also because when the value is selected our actor can easily say the words player selected. Then comes the logic of the dialogue. The dialogue itself is a loop, which loops until player selects the option 3 (Bye). So every time the loop iterates, the dialogue box is recreated and player can choose again his options.

We can see that inside of this loop we first assign 3 responses (we didn’t solve the book issue yet) and then set the game to interactive mode. But it was already interactive, so why? Because we don’t want our player to roam around while chatting, so we set the game to interactive mode only for the dialogue selecting. We wait for the player’s input and then use the switch logic to choose the response. As I already outlined, you can do anything as a response. If you decided that after certain option game unexpectedly quits to the desktop, simply put there Game.QuitGame(); but don’t blame me if players torture you afterwards.

Okay, let’s deal with the book issue. We want player to speak about the book only when she takes it. It’s actually very intuitive and it’s combining the ideas of the previous chapter too. Modify the basic function to:

Game.AddResponseOnceGame(0,options[0]); Game.AddResponse(1,options[1]); if (actor.HasItem("book")) Game.AddResponse(2,options[2]); Game.AddResponse(3,options[3]);

So we’re saying here, that only if actor holds a book in his inventory, this option should be added to the dialogue tree. Neat. And of course we need to define appropriate answer.

case 1: sally.Talk("Who exactly is of interest to you?"); break; case 2: sally.Talk("I don't know but it really looks neat!"); break; case 3: sally.Talk("See ya!"); break;

I hope you’re starting to get the feeling of the whole thing. But how about moving to the second level? We’ve decided to use a function called colleagues for it, so let’s do it.

modify the case 1: section to read:

case 1: sally.Talk("Who exactly is of interest to you?"); colleagues(); break;

Now we have to define the colleagues() function.

function colleagues() { var options; options[0] = "Marc?"; options[1] = "Peter?"; options[2] = "Dirac?"; options[3] = "Back to my other questions."; Game.StartDlgBranch(); //We’re starting a branch because of AddResponseOnce var selected; while (selected != 3) { Game.AddResponseOnce(0,options[0]); Game.AddResponse(1,options[1]); Game.AddResponseOnce(2,options[2]); Game.AddResponse(3,options[3]); Game.Interactive = true; selected = Game.GetResponse(); Game.Interactive = false; actor.Talk(options[selected]); switch (selected) { case 0: sally.Talk("He was a hero of a Sci-Fi adventure game which was never released."); break; case 1: sally.Talk("Would you believe it? Peter went missing."); sally.Talk("We're so scared!"); break; case 2: sally.Talk("Strange fellow. Sharp as a razor."); break; case 3: sally.Talk("As you wish."); break; } } Game.Interactive = true; Game.EndDlgBranch(); //We end a branch here }

So as you can see, it’s really almost identical to the basic() method. The only main difference is the StartDlgBranch / EndDlgBranch combo, which defines the start and the end of the tree branch and provides us with the nice function of having topic disappeared from the tree when we don’t need it (already read it).

Okay. You’d say that you don’t need to see the last section because of the perfect analogy to what we’ve just seen here. But I’ve decided to put a plot twist in it!

At the very beginning of this file we’ll create a new global variable called murderSuspect.

So our file starts with:

#include "scripts\base.inc" global murderSuspect;

And now we can make this function called Peter:

function Peter() { var options; options[0] = "Where was Peter last seen?"; options[1] = "Did he have any enemies?"; options[2] = "Back to my other questions."; var selected; while (selected != 2) { Game.AddResponse(0,options[0]); Game.AddResponse(1,options[1]); Game.AddResponse(2,options[2]); Game.Interactive = true; selected = Game.GetResponse(); Game.Interactive = false; actor.Talk(options[selected]); switch (selected) { case 0: sally.Talk("He was with me on the party. Then he suddenly left."); actor.Talk("That's strange. Don't you think?"); sally.Talk("Well... No... It was ... usual."); break; case 1: sally.Talk("No. Only that stupid girl who was hitting on him."); actor.Talk("A girl you say? Did you get envious or what?"); sally.Talk("Envious! Me??? On THAT girl? Never!"); sally.Talk("Besides I would kill hi..."); actor.Talk("WHAT???"); sally.Talk("Nothing!"); murderSuspect = true; break; case 2: sally.Talk("As you wish."); break; } } Game.Interactive = true; }

The only difference in this one is that we set a global variable which will influence something in the game. This is the key stone on the game logic (sometimes referred as a gaming "butterfly effect" – someone tells you a piece of information and completely unrelated drawer in another town suddenly mysteriously opens – but we’re not discussing game design related flaws, right? Right???).

The only remaining change is to the function basic(); but I’m going to post the whole script now because I believe you will be able to spot that easily.

#include "scripts\base.inc" global murderSuspect; function Peter() { var options; options[0] = "Where was Peter last seen?"; options[1] = "Did he have any enemies?"; options[2] = "Back to my other questions."; Game.StartDlgBranch() ; var selected; while (selected != 2) { Game.AddResponse(0,options[0]); Game.AddResponse(1,options[1]); Game.AddResponse(2,options[2]); Game.Interactive = true; selected = Game.GetResponse(); Game.Interactive = false; actor.Talk(options[selected]); switch (selected) { case 0: sally.Talk("He was with me on the party. Then he suddenly left."); actor.Talk("That's strange. Don't you think?"); sally.Talk("Well... No... It was ... usual."); break; case 1: sally.Talk("No. Only that stupid girl who was hitting on him."); actor.Talk("A girl you say? Did you get envious or what?"); sally.Talk("Envious! Me??? On THAT girl? Never!"); sally.Talk("Besides I would kill hi..."); actor.Talk("WHAT???"); sally.Talk("Nothing!"); murderSuspect = true; break; case 2: sally.Talk("As you wish."); break; } } Game.Interactive = true; Game.EndDlgBranch() ; } function colleagues() { var options; options[0] = "Marc?"; options[1] = "Peter?"; options[2] = "Dirac?"; options[3] = "Back to my other questions."; Game.StartDlgBranch() ; var selected; while (selected != 3) { Game.AddResponseOnce(0,options[0]); Game.AddResponse(1,options[1]); Game.AddResponseOnce(2,options[2]); Game.AddResponse(3,options[3]); Game.Interactive = true; selected = Game.GetResponse(); Game.Interactive = false; actor.Talk(options[selected]); switch (selected) { case 0: sally.Talk("He was a hero of a Sci-Fi adventure game which was never released."); break; case 1: sally.Talk("Would you believe it? Peter went missing."); sally.Talk("We're so scared!"); Peter(); break; case 2: sally.Talk("Strange fellow. Sharp as a razor."); break; case 3: sally.Talk("As you wish."); break; } } Game.Interactive = true; Game.EndDlgBranch() ; } function basic() { var options; options[0] = "Nice weather, isn't it?"; options[1] = "Can you tell me anything about your colleagues?"; options[2] = "What's this book for?"; options[3] = "You've murdered Peter!"; options[100] = "Bye!"; var selected; while (selected != 100) { Game.AddResponseOnceGame(0,options[0]); Game.AddResponse(1,options[1]); if (actor.HasItem("book")) Game.AddResponse(2,options[2]); if (murderSuspect) Game.AddResponse(3,options[3]); Game.AddResponse(100,options[100]); Game.Interactive = true; selected = Game.GetResponse(); Game.Interactive = false; actor.Talk(options[selected]); switch (selected) { case 0: sally.Talk("Not really"); break; case 1: sally.Talk("Who exactly is of interest to you?"); colleagues(); break; case 2: sally.Talk("I don't know but it really looks neat!"); break; case 100: sally.Talk("See ya!"); break; case 3: sally.Talk("Yes! And now I'll kill you as well! *BLAM*"); Scene.FadeOut(1000,255,0,0,255); Game.QuitGame(); break; } } Game.Interactive = true; } on "LeftClick" { basic(); }

Just to avoid confusion, Scene.FadeOut fades out the scene to specified color. It’s prototype is:

Scene.FadeOut(duration, red, green, blue, alpha);

and we let it fade for 1000 ms (1 sec.), to full red and no transparency.

Game.QuitGame(); simply exits the game to Windows.

Of course you can find the listing of this script in the resources folder for the chapter 7.

You can find a couple of related methods which we didn’t cover here in documentation under

Contents → Scripting in WME → Script Language Reference → Game Object in the section Responses / Inventory

And that concludes this chapter but don’t worry. There is a lor of exciting stuff to come.